When An Office Is Not A Place – But A State of Mind

WORKING AT HOME – WINTER 1995-1996

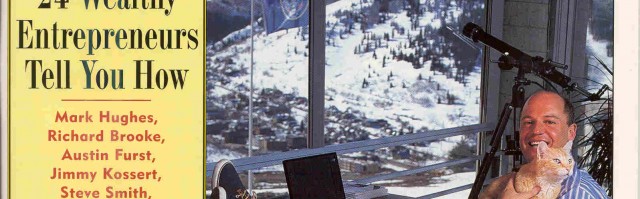

A home-based local-area network: Every room is wired for the use of electronic equipment. Ever a pioneer, Paul Zane Pilzer has blazed a brilliant trail through many careers–economics professor, real estate developer, author, adviser to Presidents, entrepreneur. Now, from the mountaintop glass pentagon he calls home, he’s breaking new ground with advice for all home-based businesses that is, as always, unconventional:

- Don’t draw a line between work and pleasure.

- Don’t separate your work from your family.

- Don’t set up an office in a separate room in your house.

- And, to network marketers: Go high technology!

Pilzer started working at home, from his New York City apartment, in 1976, after arranging to work nights as an economics professor at New York University and days as a vice president for Citibank. His desk and home looked out on the East River, and his computer required him to put his headset in a cradle that linked him into the Citibank mainframe. In the late 1980’s, he progressed into airport industrial-park development. He also helped uncover the Savings-and-Loan crisis, wrote a book about it, and became an economic adviser to the Reagan and Bush administrations. In this decade, he is helping to create an industry of CD-ROM educational disks.

His success has enabled him to build a dozen homes–in New York, Utah, and Texas, continually refining and updating his home-office concept. “Always assume that there’s a better way now than the way you set things up last month,” he says. “Allocate a specific amount of time to research communication and work technology rather than fall behind.”

Today, Pilzer’s days are a seamless weave of work and play. A 41-year-old bachelor, he gets down to business at 7:00 a.m.–carrying his IBM Thinkpad around the 12 rooms of his 8,000-square-foot house in Utah. He zaps back the answers to the 100 to 150 electronic-mail messages he gets daily from ZCI Publishing, Inc., his electronic publishing business in Dallas, and the 30 to 50 messages he gets from others.

He breaks at 11:00 a.m. to depart for the ski slopes. During the 45 minutes the lift takes to get to the top of his favorite run, he makes private business calls on his cellular phone. Then, after hiking to the top and breathing in the crisp air, he skis down–“It requires total focus, or you’d kill yourself”–to have lunch with friends. In the summer, he rides his bicycle a couple of miles up the mountain. Totally refreshed, he heads back home, where he checks the replies to e-mail messages he’s sent earlier; prints out telephone numbers; and, taking a phone with a 25-foot cord, climbs into a Jacuzzi that sits atop a cliff with a panorama of ski runs in the distance. There, he makes all of the callbacks that require a more extended amount of time–“I turn off the jets, so they won’t know where I am.”

At 4:00 p.m., he knocks off work, watches the sun set over the Wasatch Range, and has dinner with friends or relatives, perhaps followed by a laser-disk opera on his large-screen theater or a game of pool. Sometimes the event of the moment will simply be the sights–a purple storm cloud advancing, a herd of elk poking their noses against the side of his three-story glass castle, the planet Jupiter climbing high into the sky. “I’m very involved with my brothers and their children and my cousins. Because I have large houses in nice places, I encourage them to visit,” says Pilzer.

As everyone cooks, talks, and plays, he may join in or sit off to the side, receiving and sending more e-mail. At some point during the evening, he will make a 15-minute conference call to his key managers in Dallas. He’ll often break off from his business tasks to chat with his guests, finding their interest in his work energizing and inspiring. “There’s nothing more rewarding than having your family and friends rooting you on: ‘How did things go? How was that interview?’ Once we get over thinking of work as a slave-factory job,” he says, “mixing work and home is a very pleasurable experience.”

Before he goes to bed, he spends a half hour in an office on the third floor–the only time he’s actually there–checking his computer for faxes, answering more e-mail, and, for relaxation, playing around in Morse code on his ham radio.

What doesn’t his day include? The trappings of work that would cramp his style: on-site staff; voice-mail messages (“I hate voice mail–it goes on and on”); and a reliance on fax machines (“Put all over! Yuk!”). Which brings him to network marketing.

Network Marketers and High Tech

Despite its lead in the trend toward home-based offices and in remaking retailing, Pilzer believes “network marketing is behind corporate America in its use of electronic-text messages. It’s becoming too reliant on voice mail, and that’s been slowing it down,” he says. But he does see signs of high-tech growth: “Those network marketers who are developing a substantial retail business are starting to use enhanced communications such as e-mail and enhanced delivery system such as online ordering directly from the shipper.” The network marketing activity on CompuServe, he notes, grows exponentially every two to three months.

For Pilzer, technology is so key to his productivity that his entire Utah home has been designed to ease the use of his electronic-communications equipment. Every room is wired with a 10Base-T lamp connection that links all the communications equipment in the house into a local area network. That means that no matter where he roams, he can plug in his IBM 755CD laptop, which includes a CD-ROM player, a telephone, and a speakerphone. He has two freestanding computers, a Gateway 2000 Pentium P5-60 and a generic 486SX25 that he uses to back up his IBM ThinkPad’s hard drive, as well as a Hewlett-Packard laser printer on each floor: “They’re down to $450, so it’s worth the convenience of having one on each level.

“The one place there is scarcity,” he says, “is time.” So he’s developed techniques to make the most efficient use of his high-tech environment. For example, his secretary in Dallas listens to his voice-mail messages, then summarizes and e-mails them to him; she also e-mails the salient details of his faxes and paper correspondence. For office memos, he uses software called Lotus CC:Mail Mobile, which allows associates, each of whom is identifiable by a color, to comment item by item. He takes only about 30 seconds, on average, to answer an e-mail message, partly because of an OzWin software feature that allows him to lift a question out of a person’s message, double-bracket it, and type in a quick “yes” or “no.”

He scans the CompuServe bulletin boards to keep abreast of trends and gauge the response to his speeches before network marketing groups. “I can see instantly where I make mistakes–and correct them.”

The Best Open-Door Home Office

Pilzer believes “an office is not a place but a state of mind that lets you work around the house. When your office is in a separate place, it makes what you do feel like work, instead of something that you love. A room with a closed door is a depressing place to go.” In fact, he advises home-based business owners to make sure they can plug in their terminals in their kitchens, the heart of activity of most houses: “I tell people that the Compaq Presario, which you can get for about $1,500 with a CD-ROM, is the computer of choice for the kitchen. They say, ‘Paul, I want a computer for my office.’ I say, ‘Put it in the kitchen, trust me.'”