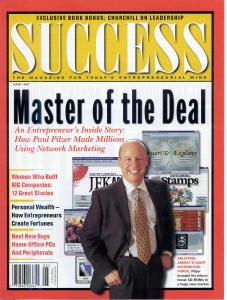

Master Of the Deal

SUCCESS MAGAZINE – JUNE 1997

January 19, 1996. A perfect ski day in Utah. Paul Zane Pilzer was on a lift, just reaching the top of the slope, when his cell phone rang.

“Paul? This is Mike Herblet from Amway,” said the voice. Pilzer jumped off the lift, sat himself down in the snow, and unhooked his skis. He had spent five years working on Amway; any call from the home-products giant could be critical.

Forty-five minutes later, Pilzer stood and took one of the greatest runs of his life. He had clinched an unprecedented deal to sell his educational CD-ROMs through Amway, among the biggest network marketing companies in the world. By itself, this arrangement does not make Pilzer the king of the CD-ROM Mountain, but it sure does lift him above the crowd. The CD-ROM market is incredibly competitive, with about 8,500 companies scrambling for a foothold. Widespread distribution is a powerful competitive advantage. Amway is a $6.8 billion giant with a vast system of distributors selling all over the world. Its one-on-one sales approach is made to order for a fresh product that is still unfamiliar to most potential customers.

“Somebody has thought this deal through very carefully,” says David Phelps, a spokesman for the Software Publishers Association in Washington, D.C. “It seems like a marriage made in heaven.”

“Amway and Paul Pilzer are using network marketing for things no one thought possible,” says Richard Poe, a former senior editor at SUCCESS and author of the best-sellers Wave 3: The New Era in Network Marketingand The Wave 3 Way to Building Your Downline. “It’s a stroke of brilliance. If it works, it raises the possibility of an alliance between network marketing and various high-tech industries that is potentially extremely profitable.”

CAPITALIZE ON YOUR DREAMS

The “marriage made in heaven” followed a long courtship. In 1991 Don Held, one of Amway Corp.’s top independent distributors, booked Pilzer to speak in St. Louis at a meeting of 3,500 distributors. Pilzer had never heard of Amway or network marketing.

Pilzer’s speech was based on his 1990 book Unlimited Wealth, which debunks the belief that the world’s wealth is limited and the next guy’s piece of the pie limits yours. Instead, he said, wealth is created anew through entrepreneurship and can best be generated through distribution, rather than manufacturing. His message spoke to the heart of network marketing, which is essentially a method of distributing goods and services.

Pilzer’s speech had the audience standing on chairs and cheering. Amway distributors bought millions of cassettes of the speech.

A few months later, at his pentagonal glass house on a Utah mountaintop, Pilzer hosted a dinner for three major players from the Amway organization: then-COO Tom Eggleston and Dexter and Birdie Yager, who head a downline estimated at a million distributors–about half the global total. Pilzer spoke about the educational CD-ROMs he had been publishing for two years. With his guests huddled around the computer, he brought a Bible software program onto the screen and typed in the word “David.” Immediately, every biblical reference to the name appeared. The Amway group was blown away.

When he was 21 and in the MBA program at Wharton Business School, Pilzer (now 43) designed a computer program that let macroeconomics students give themselves self-quizzes and provided answers that corrected wrong assumptions. “One day this technology will allow us to affordably bring the best teacher of every subject to every student,” his thesis prophesied.

But Pilzer was at Wharton “to learn how to get rich.” After graduation, he worked for Citibank in New York, rising to second vice president within two years. He began teaching economics at New York University in 1979. He soon left Citibank and moved to Texas, earning his first million in real estate by age 26. He later served as an economic adviser to presidents Reagan and Bush and wrote three best-selling books, Unlimited Wealth,Other People’s Money, and God Wants You to Be Rich: The Theology of Economics. He continued teaching at NYU during the fall semester, often commuting across the continent or the Atlantic to be at the podium on Mondays. In interchanges with students, he’d swivel around to write key words on the blackboard. Afterward he’d head to his mother’s house on Long Island. “You must have had a good class tonight,” she’d say. “Your covered in chalk.”

Pilzer realized that interaction between students and teachers was the key to learning. He knew this interactivity could be replicated on a computer, but at the time the only interactive software was being developed for the now $15 billion international video-game industry. Seeing his friends’ children engrossed in Nintendo, he realized the appeal of a computer game: It had unlimited patience and offered its undivided attention. Why couldn’t the same technology be used to get kids engrossed in algebra?

FIND THE RIGHT DISTRIBUTOR

He tested his theories in 1989. Sony executives invited him to be one of the creators of software for the Sony MMCD Player, a handheld, DOS-based device designed to play CD-ROMs. The disk he produced featured motivational author Anthony Robbins, who interviewed Pilzer about his economic views. At various spots viewers could point and click to see printed works by both men.

The disk, Pilzer says, was the country’s seventh-best-selling CD-ROM in 1992. He soon developed the PowerCD Operating Environment, an interactive model that became the foundation of his Dallas-based company, then called Zane Publishing Inc. The PowerCD runs in any platform–DOS, Windows, Mac.

A glowing review in PC Magazine attracted venture capitalists’ interest. He turned them down: “My view always was, in an obnoxious way, that I’m richer than most of these investors–why would I take their money unless I didn’t believe in the deal?”

Pilzer tried to license the PowerCD to such large educational publishers as Simon & Schuster, Macmillan, and Prentice Hall. Maybe they could produce their textbooks as CD-ROMs. When none agreed, he asked them to give Zane the right to put their textbooks on CD-ROMs and sell them in nonschool markets. As a result, he says, his company owns the electronic rights to “probably the largest collection of curriculum-based intellectual property in the world”–many of the major textbooks used by American students, as well as the Merriam-Webster dictionaries.

Pilzer’s products are not flashy. Other children’s educational CD-ROMs are undeniably more sophisticated. Zane Publishing has never won a “Codie,” the software industry’s equivalent of an Academy Award. It is seldom mentioned in the same reviews as industry leaders The Learning Company, Disney Interactive, or Broderbund. About a quarter of Zane’s CD-ROMs have full-motion video, but many resemble slide shows with running text and voice-overs. Warren Buckleitner, an award-winning reviewer of children’s educational software, says of Zane: “They have their heart in the right place, and they’re good at putting a lot of content on a disk and making it accessible. But I haven’t seen anything from them that has really knocked my socks off.”

But Pilzer’s CD-ROMs are based on, and used with, popular textbooks by established teachers and can be easily integrated into a curriculum. They are highly specific: There are disks on Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre, on surrealistic art, on plant anatomy. Each has quizzes–a new one can be clicked on every 15 seconds–usable by a student at home or a teacher in a classroom.

When Pilzer started Zane in 1989, he assumed that Blockbuster Video stores would bring CD-ROMs into every neighborhood. But Blockbuster decided against stocking them after three unsuccessful 50-store trials in California. The sale of Zane’s CD-ROMs in computer stores and other retail outlets has met only limited success. As late as 1996, Zane had 0.1 percent of the $3 billion CD-ROM retail market, ranking 106th among 655 companies, according to SoftTrends, a software tracking service in Port Washington, N.Y.

Which is why Amway began looming larger and larger in Pilzer’s strategy. Amway has 2.5 million distributors who sell its household products, as well as products and services from other companies–from travel packages to breakfast cereals.

DRAW INSPIRATION FROM REJECTION

But getting Amway on board would prove to be daunting: In fact, Pilzer says, he was in touch with the corporate side “continuously for five years–and I always got no for an answer.”

He adds: “If you apply for a job or a business opportunity and don’t get rejected the first time, you’ve sold yourself short and applied too low. If you’re shooting for the moon, something above your current situation, you have to work hard and make it happen. That’s how you know it’s the next step for you.”

He learned that lesson at age 19, when he was initially rejected by Wharton’s MBA program. He pulled out every stop to finagle an interview with the admissions head and, two days later, talked his way into the school. But the whole time he was at Wharton, he recalls, “I had a second-class-citizen attitude. I thought, these people really belong at Wharton. They deserved it; I didn’t. I had to manipulate my way in.” He worked so hard to prove himself that he graduated in one year at the head of his class. In the years afterward, he says, “each thing I got, I manipulated or pushed my way into–and it wasn’t until I was 15 years out of Wharton that I realized that everything worth doing in life is going to get rejected the first few times. The rejection is proof that you’re pushing the envelope. There comes a time in entrepreneurship when rejection is no longer painful–in fact, the rejection-fighting-acceptance process becomes enjoyable.”

His biggest hurdle with Amway was not having enough different disks to offer customers. For four years Zane worked to create programs. But 1994 it had 120. Amway wanted more.

Besides the executives, Pilzer had to win over a board of top distributors. The courtship began with dinner at his house in 1991. That night he asked for and wrote down the names of the Yagers’ and Eggleston’s children and grandchildren. He did the same with the families of other Amway “diamond” distributors and executives. Whenever he released a new CD-ROM, he sent it to those children, sometimes starting an e-mail correspondence.

Pilzer also lectured to Amway distributors about twice a month. He estimates that he spoke to more than a million between 1991 and 1996. After finishing a speech at noon, he says, he’d sometimes sign books until 3 A.M. If distributors liked his CD-ROMs, he’d encourage them to tell Amway’s corporate side.

He learned that lesson during a visit from John Grillos, a venture capitalist who is now general partner at ITech Partners of Menlo Park, Calif. Pilzer had a check in his hands for $250,000 from Apple Computer. Apple had manufactured what it called PowerCD hardware to go with its PowerBooks; its lawyers hotly pursued Zane Publishing to prevent Zane from using the name to describe its CD-ROM software. Pilzer’s lawyers discovered that Zane had the trademark for the name. “We agreed to drop charges against them for trying to close our business: the deal was, they had to deliver $250,000 that weekend with an apology letter,” Pilzer says. “So I’m feeling pretty good and telling the story to John Grillos. He says, ‘You did what? Do you realize how important Apple is in the school market?'”

As Pilzer tells it, Grillos called a top executive he knew at Apple and said, “I’m sitting in the office of Paul Pilzer, chairman of Zane Publishing. He has a $250,000 check from you, and he wants to apologize. He wants to return it… What’s the deal? He’s got the best education software in the world, but it’s not done yet and won’t be done for a year, so you’re going to buy $1.25 million of it right now and make this $250,000 a deposit.” The deal would mean that Apple’s books would not show a quarter-million loss because of a mistake, and Zane’s books would show hefty advance orders from an industry heavyweight.

Afterward, Pilzer recalls, “I said, ‘You’re amazing.’ He said, ‘Paul, every transaction in business can be turned into a win-win.'”

Grillos invested in Zane, joined the board, and attracted other Silicon Valley investors. Pilzer estimates venture capitalists have put in about $6 million. Zane expanded its CD-ROM offerings steadily. Then, in August 1995, Amway COO Eggleston suddenly left the company and the founders’ two sons assumed leadership.

Suddenly, Pilzer says, “I was not on the radar screen.” Five months later later he had resigned himself to working out deals with other network marketing companies–and then came that surprise call on the ski slope. To this day, he says, he has no idea what went on inside Amway that led to the turnaround.

We reviewed Paul’s CD-ROM educational program and decided it would be a good fit for our distributors and customers,” says Bill Gerst, Amway’s merchandise manager. “Many have school-age children.” On March 28, 1996, Amway agreed to carry the CD-ROMs, securing the right to keep selling them if he goes out of business.

The product was launched the following July with a catalog that included 180 CD-ROMs covering half the curriculum of grades K through 12, including 24 in biology, 42 in history, and 34 in literature. Each CD-ROM sold for $15. A “family pack” of 132 was priced at $1,000. It became the surprise top seller.

Amway also connected Pilzer with other CD-ROM publishers, including Logos Research Systems, a major religious publisher, and Kaplan Educational Centers, which publishes preparatory material for standardized assessment tests. Today Zane manufactures those companies’ CD-ROMs and distributes them through Amway, paying the companies a royalty on sales.

REACT QUICKLY TO MARKET TRENDS

Another potential “windfall,” in Pilzer’s words, arose when major textbook publishers noticed a new trend. Increasingly, school administrators are allowing teachers to select computer software, rather than buying a bundle of programs for the whole district. A typical school publisher’s sales force of fewer than 500 is hard pressed to reach the country’s 2.75 million teachers. A number of companies, including Simon & Schuster and Prentice Hall, decided to allow Amway distributors to sell Zane CD-ROMs directly to teachers and schools.

The market is young. Many schoolrooms don’t have computers, or they have outdated models without CD-ROM drives. “Schools are inching forward,” says Jamie Horwitz, a spokesman for the American Federation of Teachers. “To most of our members, technology still means getting a telephone.”

But it is undeniably a growing market. To help distributors reach it, Zane put out a school catalog in January. Amway distributors pitch teachers on how the CD-ROMs can save time. With a few points and clicks, a teacher can print instant quizzes.

In nine months of selling, Amway distributors accounted for a third of Zane’s sales. So far, 100,000 Amway distributors in the United States have bought the CD-ROMs, he estimates, and of those, 30,000 are actively selling them.

Pilzer says Zane’s sales have increased from about $300,000 in 1994 to $6.5 million in 1996. He estimates that more than 10 million CD-ROMs have been sold to date.

KNOW YOUR CUSTOMER

In January Zane was acquired by Zane Interactive Publishing Inc., a public company that had raised capital for an Internet product that never materialized. A secondary offering planned for the third quarter of 1997 is designed to raise $10 million to build distribution channels, says Pilzer, who now receives a $12,000 monthly salary and owns 19 percent of the company. He recently left his CEO position to act as publisher and chairman, which gives him more contact with children and teachers.

“I spend half my week listening to them–reading their letters, calling them up,” he says. “I’m the one who has to ensure that the product works in educating children before it gets into the marketplace.” Last year he became an Amway distributor in the Yagers’ and Don Held’s downline. “Many people I meet want to get titles, and the least expensive way is through Amway,” he says.

Pilzer’s previous careers have lasted five to seven years. “I’m two years overtime,” he says, “I can honestly say I don’t see an end in sight.”

“Everything I’ve done in life that has been worth doing, I faced rejection in at the outset. It used to be painful. Now I revel in it. It means I’m reaching for the stars. Go after the thing worth going after–not the things others think you deserve!”

High-ranking Amway distributors like Kathy and Jody Victor (left) Susan and Hal Gooch (with Pilzer) and the Broomes (below) have helped promote the CD-ROMs, Pilzer says. Steve Van Andel, current chairman of Amway Corp., with Pilzer (right).

Distributors Diana and Clarke Broome. Paul Pilzer spoke about his CD-ROMs at a meeting organized by Hal Gooch in Atlanta in January. Pilzer estimates that 34,000 people attended.